ON LOCATION IN 1989

I meet BBC make-up designer Julie Vincent

If your actors look spotty, shiny and unattractive on screen, then perhaps they need a little make-up. But where do you start? I visited BBC North-West to find out.

The location: the BBC's Liverpool studios; a hangar-like building on the Mersey Docklands, filled with outside broadcast lorries and portacabins, one of which is the make-up room. The programme: On The Waterfront, the Saturday morning children's show. The expert: make-up assistant Julie Vincent, acting as make-up designer on this programme.

In her ten years with the BBC, Julie has worked on a wide variety of programmes: from Hi De Hi to The Sword Divided and Top of the Pops. She chatted with me as she busily made up actor Andrew O'Connor.

"We put make-up on people on programmes like the news, so that their skin has a good finish to it," Julie told me. "It takes away the shine. Lights in the studio do put a lot of glare on the face, so the majority of people do need something."

Julie studied my haggard features for a moment (the result of too many late nights trying to meet magazine deadlines). "If you came to be interviewed on television, I'd probably use a very light base on you, hiding any blemishes or bags under your eyes with a colour corrector, usually slightly paler than your own shade of skin. Then I'd powder lightly with a loose powder on a puff and finally dust off any excess powder. We don't put very heavy make-up on men for normal interviews.

"We have some anti-flare creams which stop the shine on the skin. Sometimes, if a man has a good complexion, with no blemishes, you just need a little of this on the temples, which pick up light. The creams we use can be bought from a shop in London called Cosmetics a la Carte.

"Every person has a different tone to their skin and now there are lots of make-ups for Black or Asian skins. Shades of Black comes to mind, Fashion Flair is another."

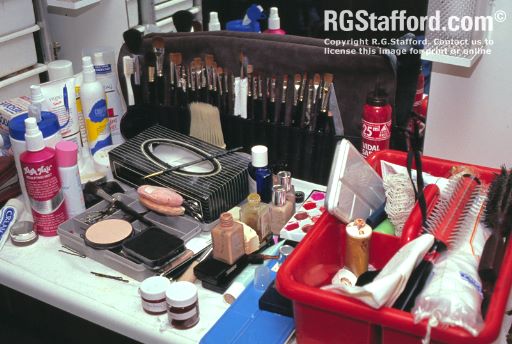

Julie's own impressive array of brushes and cosmetics were laid out neatly in front of the mirror. "People think we use very heavy make-up, that's a fallacy," she told me.

"In television, the camera is very critical and goes in close, so make-up must be applied quite lightly and it must be well applied. In fact, we use ordinary make-up of the kind you might buy in any of the department stores. We all have our favourites, make-ups which sit well on various skins, such as Clinique or Elizabeth Arden. We use Max Factor face powder a lot and Clinique."

Does that mean that women can wear their own everyday make-up in a similar interview situation? "If it's well-applied, then certainly," says Julie. "If a lady has a nice skin, then she might not need a foundation on, just a bit of shaping to her face. A little shader or blusher just to highlight the cheekbones."

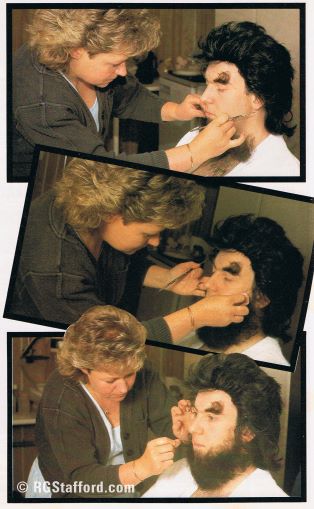

By now, Julie was adding a beard to Andrew O'Connor, who was already sporting a bushy black wig and a pair of eyebrows which would put Dennis Healey to shame.

She continued: "If it's something like Open Air, then people generally find it quite exciting to be made up by us, because it's an experience for them. Sometimes we get people who won't wear make-up, we don't force them. Nowadays we get a lot of people asking for the Beauty Without Cruelty range, which we have a stock of."

On the other side of the cabin, make-up assistant Jill Sweeney was getting Terry Randall ready for his role as an interviewer with a receding hairline. First, Terry's own hair was covered with a bald-cap made of thin rubber.

"We make these ourselves," Jill explained, as she fixed it in place with spirit gum.

She added a ginger hairpiece and applied some make-up to 'hide the join'. The result was remarkably natural-looking and would go unnoticed in the street, although Jill said she would be able to tell.

These hairpieces cost several hundreds of pounds. Sometimes they're specially made, although the BBC has a large stock in London which the department can order from. The hairpieces are tried out on the actors at pre-production wig-fitting sessions.

Jill and Julie were using a number of different wigs for a comedy sketch sending up what happens when continuity goes wrong. The sketch called for lots of quick changes - giving the make-up team between twenty and thirty minutes each time.

We walked outside into the sunshine for one Monty Python-type shot. Two chairs had been placed on the road, with the Mersey in the background. Jill was clutching face powder and powder puff, ready to dab any forehead which dared to perspire.

I'd always thought pan-cake make-up was used extensively in television, but there was none to be seen that morning. "That's used a lot in the theatre," Julie told me. "We only use it to get certain finishes. If we wanted a matt finish we'd use pancake - for a clown for example.

"I worked on Gulliver's Travels. If you imagine that period, with the pompadour wigs and pale skins which they powdered a lot. We used pancake to get that 'look'."

The shot completed and back in the portacabin, Jill began cutting up the back of Terry's bald-cap, so she could remove it. It was a bizarre scene, as the scissors appeared to be disappearing into his apparently bald head. It was also a painful process, because the spirit gum had stuck to the hairs on the back of Terry's neck.

On a dummy head, on the bench, there was another bald-cap, to which Julie had added a thick wax forehead. Beside it, a shiny black wig and a photograph of Herman Munster. All in readiness for a Frankenstein's monster sketch later in the day. Drama and special effects are much more demanding than interview or news programmes and research is often necessary, as Julie points out.

"If a drama's set in a particular period, then you need the make-up and hairstyles which actually match that period. For example, 1930's and 1940's make-up differs drastically from today's. Sometimes you can dress the artist's hair in the particular style but, nowadays people streak their hair and they wouldn't have highlighted it like that in the past. We use a lot of wigs for drama."

It takes years of training and experience on the job, before you can reach BBC standard. Julie Vincent has had a lot of training, even to do a normal, straight make-up on a person.

"You might think that a news presenter can do her own make-up, but we could look at it and think 'well, her eyes aren't defined correctly, she's put the shader in the wrong place, her lip line's not even..."

If you're shooting a production that has a budget, then you might consider hiring an expert like Julie. Until then, there's no reason why, as a beginner, you shouldn't experiment and have plenty of fun in the process.

Like so many things in television, make-up is at it's best when it goes unnoticed by the viewer. As Julie says: "The hardest thing is to make somebody look natural when they've really got quite a lot of makeup on."

TOP TIPS FOR DIY MAKE-UP FOR VIDEO

- Ordinary make-up from department stores and chemists is quite adequate. Ask whether they have any leaflets on the correct application of it.

- Even in the most basic video, kill shine with a little face powder on a powder puff and keep it handy, ready to dab perspiring faces between takes.

- Use a colour corrector to hide any spots or dark shadows under the eyes. A light base is enough in many situations.

- Be especially careful when using make-up on men. If possible, use a colour monitor to check that your subject looks completely natural in close-up on camera.

- If you're shooting a period drama, old photographs or paintings are a good starting point. Wigs can be hired from theatrical costumiers.

- Enhance your efforts by imaginative use of lighting, camera angles and locations.

Thanks to the BBC and the professionals who helped with this article. It appeared in the April 1990 issue of the UK magazine Video Maker. All rights reserved.